Every year the University of Hartford awards one or multiple graduate students the Tai Soo Kim Travelling Fellowship—a travelling fellowship that supports a Master of Architecture student’s travel expenses up to $6,000. When our team member, Molly Straut, graduated in 2021, she and her fellow classmate were the student team that was awarded the Tai Soo Kim Fellowship. Their proposal was to travel to Aotearoa New Zealand to explore their regenerative and sustainable design practices. Given the international travel restrictions during the pandemic, Molly and her classmate’s trip was postponed until this past January 2023. Please note that throughout this article we’ll be referring to New Zealand with its’ Maori name: Aotearoa—meaning land of the long white cloud, out of respect for the indigenous Maori culture and the name given to the country many centuries ago.

Why Aotearoa New Zealand—Elevating Indigenous Environmental Practices

The decision to pursue research in Aotearoa New Zealand was based on the country’s inclusion of regenerative and sustainable practice throughout its cultures, infrastructure, and environment. Aotearoa New Zealand has been at the forefront of incorporating sustainability policies within its government, and is in pursuit of 100% renewable energy by 2030. This focus within the culture is directly influenced by the Māori people—the indigenous population of the islands. The Māori believe in the close connection that people have with our environment; through multiple movements of activism, they were the driving push for the country’s shift to focus on conservation of the environment. This is reflected all throughout the country’s culture—especially through its architecture.

Auckland

Home to Aotearoa New Zealand’s largest and busiest airport, many visitor’s first stop is the city of Auckland. The city sits between two harbors, and with much of its development occurring in the mid to late 20th century its architecture is mainly composed of new-age modern structures with remnants of classic influence and many that pay homage to Maori culture.

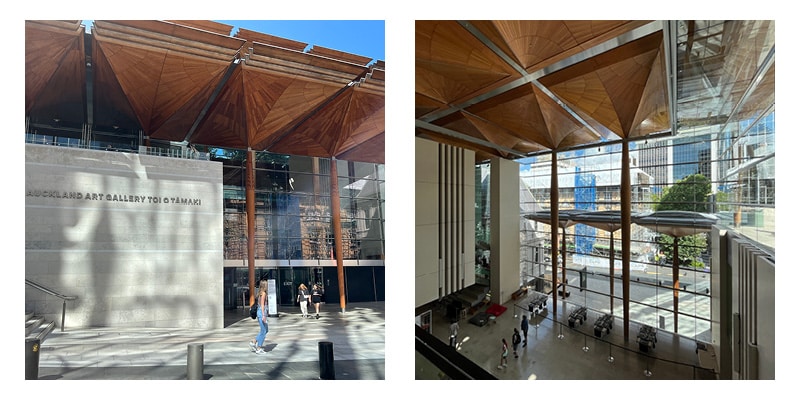

The Toi O Tamaki Art Gallery is a 2011 restoration project by architects FJMT and Archimedia of the existing historical French-Chateau style building—a municipal building that housed offices, a library, and a small gallery, built in 1888. This building has become an integral part of the city, and a great example of the influence that the Maori cultural movement and activism had on the architecture of the city. The restoration project provided a new roof and addition, with large canopy-emulating wood columns at the new entrance. The columns speak to the country’s native trees while providing a grand, shaded, entry stair. The addition also served to integrate the building with the surrounding nature, as it was built into the existing adjacent Albert Park through a series of stepped stone podiums that blend the building into the natural landscape.

Driving Out of the City

Stepping outside of city, you’re greeted by cows—and more cows. With roughly 80% of the landscape unpopulated, development outside of its main cities drastically drops off. A major aspect of the country’s care for the environment is the fact that much of it is left preserved, with farmland and small towns scattered throughout. Driving down the North Island to the South provides many opportunities to see and experience rural life and the awe-inspiring landscape.

In Rotorua, there is the opportunity to experience a part of the traditional Maori lifestyle. Whakarewarewa is a village in Rotorua that’s home to a community of Maori people who still utilize traditional, communal methods of Maori life. They are kind enough to offer experiences to tourists to share these aspects of their culture. They function with extremely low waste and low energy use– utilizing the surrounding natural geothermal pools for aspects of everyday life. Formed channels from the geothermal pools to outdoor basins are used to cool water just enough for bathing, while steam and the ~200 Degrees F geothermal pool itself are used to cook–either slowly throughout the day or in minutes!

While the community lives in modern housing structures, preserved traditional Maori houses remain on site to show traditional methods of construction. One such example is a wharepuni—or sleeping house. Like many Maori structures, these houses were designed low to the ground, often at standing height, with small and low windows and entrances that passively helped keep occupants warm against the intense winds of the landscape. These design principles carry through other Maori structures, including in Wharenui, a sacred communal meeting house. These meeting houses utilize similar passive design methods with low doors and windows, and a large exaggerated gable roof. They also show the detail and importance of wood carved ornament in Maori architecture; the exterior columns, trim, and structural pieces of a Wharenui are covered in intricate Maori wood carving. Maori ornament is seen not only in traditional Maori buildings, but also carried through modern design elements in much of the country’s architecture.

Preserving Nature Within the City

A stop you definitely don’t want to miss, Wellington is located at the southern tip of the North Island. It houses the world’s first fully enclosed, urban eco sanctuary. ‘Zealandia’ sits elevated above much of the city of Wellington, developed around the long developed Upper Dam of Wellington. The site, while only covering a couple square miles of the city, has a large goal in restoring the biodiversity of 225 ha of forest that once flourished. Approaching the entrance to the site, you’ll find yourself driving through winding one lane roads—often amongst rainfall, parked cars, and residential neighborhoods. It’s clear that there were many environmental challenges to consider in developing a city within this environment. The visitor’s center greets you at the entrance as a beautiful example of architecture working to create a symbiotic relationship with its environment. The building was designed by Jasmax Architects in 2010 and required significant consideration to the extreme flood conditions of the site and 50 m proximity to a fault line. This resulted in a large floor plate and deep foundations. The façade of the building utilizes natural and warm materials, wrapped with local wood and a curtain wall that leads into the sloped site. When walking through the building the sound of the windows’ mechanics can be heard throughout the day from an automated window system, as the building heavily relies on natural ventilation throughout the year.

These are just a handful of the amazing sites and buildings Aotearoa New Zealand has to offer; we’d encourage anyone with the opportunity to visit the beautiful country and experience it for yourself.

How have our travels as architects informed our work? Check out some of the projects we’ve completed. If you have questions about our portfolio of architectural design services, please contact us at your convenience.